While enjoying a day off from school or work this Labor Day, be sure to take a moment and reflect on the circumstances that brought the holiday to the U.S. The Pullman Railway Strike of 1894 ended with 250,000 people walking away from their jobs, orders from the U.S. president, and the lives of 30 people ending.

George Pullman is referred to by some as the father of the American railroad. Pullman was undoubtedly a brilliant marketer; he grew his business from a few train cars to his name becoming synonymous with the idea of ultimate luxury. However, Pullman was a shrewd, if not cruel, business owner who took advantage of a nation after the civil war. The low wages he paid to porters and other rail workers resulted in tipping becoming a cultural norm in the U.S.

Life in the Pullman factories was not much better. Pullman even built his own town (Pullman, Illinois) to give his factory workers a place to live close by the factory. Pullman controlled all aspects of life here where something as simple as an unkept lawn could result in a call from your boss.

Trouble began in 1893 when two of the country’s largest employers closed their doors – the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and the National Cordage Company. What resulted is the Panic of 1893, when panic hit the stock market causing economic crisis. One of the first things affected was the demand for Pullman’s rail cars. Pullman reacted with layoffs and wage reductions but did not lower the rents he charged his employees. Employees were left with next to nothing. One employee claimed that after rent was deducted from his paycheck, he still owed the Pullman company two cents.

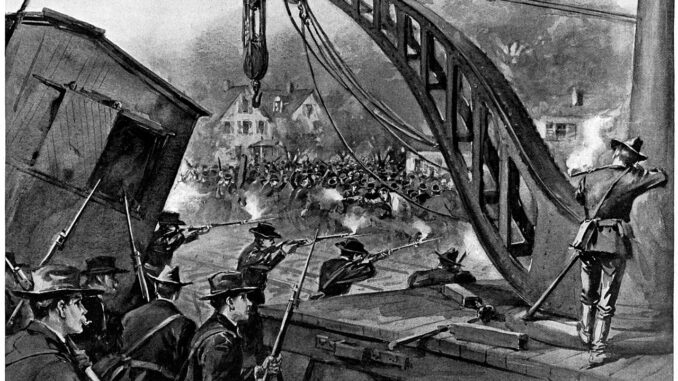

Pullman employees joined forces and walked away from their jobs in revolt on May 14, 1894. Other cities and labor unions had sympathy strike to show solidarity with their Pullman brothers and sisters. Unfortunately, George Pullman went to his friend U.S. Attorney General Richard Olney who declared the strike illegal and later convinced President Grover Cleveland to send in the National Guard. It is important to note that all goods were transported across the U.S. via train at the time – including the mail. President Cleveland stated, “If it takes the entire army and navy to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that card will be delivered.” Ultimately, 30 people, primarily in Pullman’s hometown of Chicago, died in the riots after being shot or bayoneted. Thousand more lost their jobs or were injured.

The federal commission that investigated the strike judged that his company’s paternalism was “behind the age.” A court soon ordered the company to sell off the model town. When Pullman died three years after the strike, he left instructions that his body be encased in reinforced concrete out of fear it would be desecrated. – Smithsonian

The strike resulted in no gain for the Pullman employees. The U.S. Congress also passed a federal law requiring compulsory mediation in railway disputes which pushed the federal government into taking a more impartial role in labor and business disputes. Congress also made Labor Day (the first Monday of every September) a national holiday; however, that did not help the employees regain their wages or pay their high rents. It did succeed in destroying George Pullman’s reputation.