The role of the railroad during the Space Shuttle era is well known and well documented. For nearly three decades, solid rocket booster (SRB) segments were transported from a space and aviation research plant in Promontory, Utah to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) on the tracks of Union Pacific, Kansas City Southern, Norfolk Southern, CSX, and the Florida East Coast Railway. The reusable segments traveled the route on custom-built cars and were accompanied by a team of technical experts who monitored the cars and segments as they made the seven-day trip to Florida. Upon arrival, every car was inspected, and spacer cars were added to redistribute the weight of the train so it could traverse one final hurdle: a drawbridge over the Indian River and into the restricted zone.

Once at KSC, four booster segments, each 12 feet wide and 150 tons, were stacked vertically in the Vehicle Assembly Building. Two complete boosters were joined with the external fuel tank and the orbiter and rolled out to the launch pad standing 184 feet tall. After launch, the SRBs were recovered from the ocean, broken down into their segments, and transported by rail back across the country to the Thiokol facility (now Northrop Grumman) where they started.

During the peak of the Shuttle program, the NASA Railroad operated 38 miles of industrial trackage constructed to 60 mph standards, though NASA’s track speed is just 25 mph. Trains carried four to five million pounds of hazardous materials and were more often seen creeping along at 10 to 15 mph. The last shipment of booster segments arrived in 2010, and the final flight of the Space Shuttle launched July 8, 2011. Lacking booster traffic, the NASA Railroad ceased operations in 2015, and though much of the trackage remains, many of the specialized rolling stock have been donated to museums, transferred to NASA’s commercial space partners, or sold.

But the NASA Railroad was activated long before the Space Shuttle was even conceptualized.

In 1963, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and Kennedy Space Center were in the midst of a construction boom. The Space Race was in full swing: the Russians had launched a man into space before the Americans and soon, Alexei Leonov would become the first cosmonaut to perform extravehicular activity (a spacewalk). NASA was playing catch-up. To be the first to put a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth, NASA would need bigger launchpads, training centers, testing facilities, assembly buildings, hangars, trenches, a launch operations center, offices, storage spaces, and other massive structures. NASA had recently purchased nearly 84,000 acres of land at the Cape and developed a master plan that included a railroad system to provide railroad car delivery of construction supplies for the new spaceport. As the Apollo program progressed, the railroad would be used to deliver equipment for the launches.

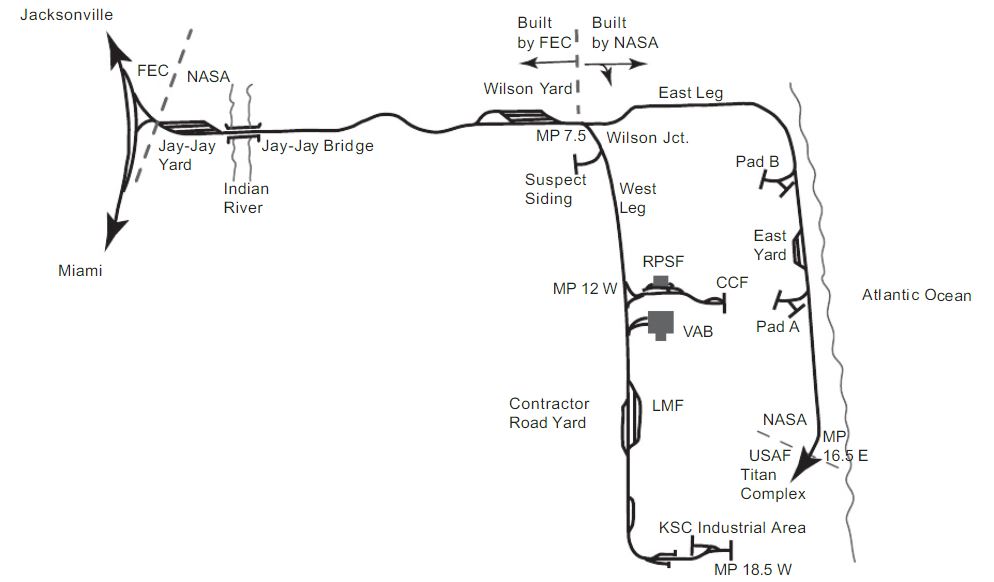

NASA reached an agreement with the Florida East Coast Railway for the construction and operation of a railroad within Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS). The FEC would construct a 7.5-mile connection from its mainline near Titusville that required building a drawbridge over the Indian River, part of the Intercoastal Waterway, to Wilson’s Corner on the east side of the river. There and at the junction near Titusville, the FEC would construct two seven-track yards using material salvaged from the removal of the FEC’s mainline double track. The FEC provided maintenance, crews, and locomotives for arriving and departing freight traffic.

The US Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE) was responsible for building the 28 miles of trackage planned within the Kennedy Space Center. An eastern and western branch were conceived: the eastern branch would connect Launch Pads 39A and 39B at KSC with the CCAFS and Titan Launch Complex closer to the coast, and the western branch would link the massive Vehicle Assembly Building with the industrial section of KSC.

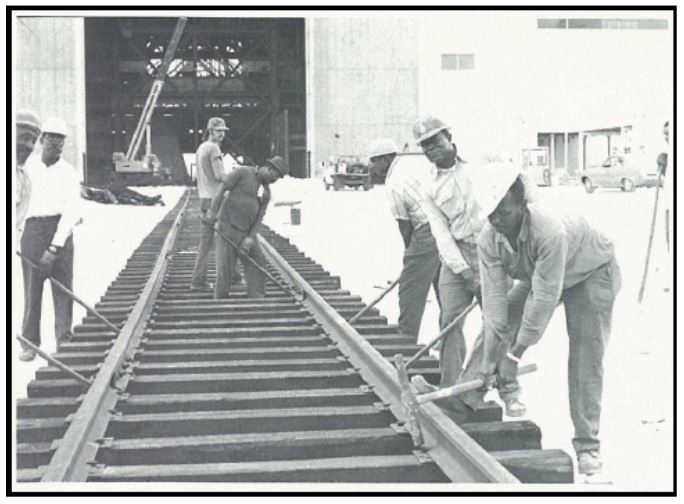

The ACOE awarded the railroad construction contract to Jacksonville’s B.B. McCormick and Bailes-Sey with the condition that the railroad be completed within 180 days, around January of 1964. This deadline coincided with the delivery of large quantities of construction materials, including steel for the Vehicle Assembly Building. While the railroad was not completed within this ambitious time frame, it was finished in its its entirety by the following year.

The NASA Railroad carried around 30,000 carloads of materials in its first five years, including the Tennessee river rock used to cover two 40-foot-wide lanes of the 7.6-mile-long Crawlerway four to eight inches thick. One Saturn V rocket required 56 railroad tank cars of propellant. Railroads were involved even when materials were shipped on roads; rocket parts were trucked to KSC from various manufacturing centers around the country with the help of local law enforcement and flagmen from nearby railroads who were assigned the special duty of facilitating the safe transport of the rocket materials and the accompanying entourage over a crossing.

Railroads also played a role in Apollo astronaut training. The ‘sandpile’ was a large, flat area of sand at KSC where various tools intended for use on the lunar surface were tested by scientists and astronauts. Florida sand, however, did not present a realistic sampling of rocks astronauts might encounter on the Moon. If the geologists in charge of training Apollo crew members wanted the astronauts to get some real practice with the instruments, they would need to bring in rocks from other regions. Gordie Swann, the Principal Investigator of the lunar Field Geography experiment and part of the team involved in selecting lunar landing sites, had been stationed in Flagstaff in support of the manned spaceflight program and was tasked with developing lunar geologic exploration procedures. Swann arranged to have two gondolas full of rocks and ballast from an Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway quarry shipped to Florida. For more variety, Swann brought in a carload of anorthosite from California. Dump trucks of other rocks arrived from around the country. Astronaut John Young, the ninth man on the Moon, joked that “a million years from now somebody will be trying to figure out what all those fancy rocks are doing in this sand.”

The railroad system at KSC remained as originally constructed until 1974 when a spur was built to haul runway-building materials to the future site of the Shuttle Landing Facility. Later, in 1983, NASA bought the FEC portion of the railway and upgraded the line in preparation for Space Shuttle operations.

The future of the NASA Railroad is uncertain. The trains left years ago, but NASA maintains about 17 miles of the once-38-mile network. A possible extension of the line to Port Canaveral has been explored. And the railroad could potentially carry booster segments again for NASA’s next giant leap: the Space Launch System (SLS). This heavy-lifting rocket will use two 5-segment SRBs to provide 75% of the vehicle’s liftoff thrust. Today, the SRBs are undergoing testing at Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems in Promontory, Utah at the same facility where the Space Shuttle SRBs began their 2,800-mile journey to the Kennedy Space Center. The research plant is only a ridge away from the Golden Spike National Historical Park — the 15-minute drive is just enough time to reflect on the sprawling landscape’s transportation heritage, where transcontinental past meets interplanetary future.

Sources and further reading:

Gordon Swann, Geology Teacher to the Astronauts. Paul D. Spudis, 2014. AirAndSpaceMag.com.

https://www.airspacemag.com/daily-planet/gordon-swann-geology-teacher-astronauts-180951646/

Historical Survey and Evaluation of the Jay Jay Bridge, Railroad System, and Locomotives, KSC. Archaeological Consultants, Inc., 2012. Prepared for NASA KSC Environmental Management Branch. https://www.scribd.com/document/266805893/Historical-Survey-of-KSC-Railroad-pdf

Interview with an SLS Engineer: How Booster Test May Help Drive Golden Spike for Interplanetary Railroad. Jason Davis, 2015. The Planetary Society. http://www.planetary.org/blogs/jason-davis/2015/20150310-sls-booster-engineer-interview.html

The NASA Railroad. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2013. NASA Facts: FS-2013-04-075-KSC. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/NASA-Railroad.pdf

NASA Railroad Keeps Shuttle’s Boosters on the Right Track. Anna Heiney, 2010. Space Shuttle Era: Celebrating a Technological Marvel. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/flyout/railroad.html

NASA Railroad Rides into Sunset. James Dean, 2015. Florida Today. https://www.floridatoday.com/story/tech/science/space/2015/05/23/nasa-railroad-rides-sunset/27784213/

Route of the Rockets. David C. Lester and Clark McClure, 2018. Trains Magazine, January 2018.

Science Training History of the Apollo Astronauts. William Phinney, 2015. John Young Interview, March 16, 1995 w/ William Phinney. https://ston.jsc.nasa.gov/collections/TRS/_techrep/SP-2015-626.pdf

Solid Rocket City: The Utah Space Center Fighting for Its Life. Joe Pappalardo, 2018. Popular Mechanics. https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/rockets/a19676079/orbital-atk-promontory-utah-sls-nasa-solid-rocket/

Stages to Saturn. Roger E. Bilstein. The NASA History Series. https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4206/sp4206.htm

Be the first to comment